Reading Comprehension Question for Anthony Burns Book

This mural, created over lxxx years afterwards John Brown's decease, captures the violence and religious fervor of the man and his era. John Steuart Curry,Tragic Prelude, 1938-1940, Kansas State Capitol.

*The American Yawp is an evolving, collaborative text. Please click here to improve this chapter.*

- I. Introduction

- 2. Sectionalism in the Early Republic

- 3. The Crisis Joined

- Four. Free Soil, Complimentary Labor, Gratuitous Men

- V. From Sectional Crisis to National Crisis

- Half-dozen. Decision

- VII. Primary Sources

- VIII. Reference Textile

I. Introduction

Slavery's western expansion created problems for the U.s. from the very first. Battles emerged over the westward expansion of slavery and over the part of the federal government in protecting the interests of enslavers. Northern workers felt that slavery suppressed wages and stole state that could have been used past poor white Americans to achieve economic independence. Southerners feared that without slavery's expansion, the abolitionist faction would come to dominate national politics and an increasingly dense population of enslaved people would lead to encarmine coup and race war. Constant resistance from enslaved men and women required a potent pro-slavery government to maintain order. As the Due north gradually abolished human bondage, enslaved men and women headed n on an hole-and-corner railroad of hideaways and safe houses. Northerners and southerners came to disagree sharply on the role of the federal government in capturing and returning these liberty seekers. While northerners appealed to their states' rights to decline to capture people escaping slavery, white southerners demanded a national commitment to slavery. Enslaved laborers meanwhile remained vitally important to the nation'south economy, fueling not just the southern plantation economy but likewise providing raw materials for the industrial North. Differences over the fate of slavery remained at the heart of American politics, specially every bit the United States expanded. After decades of conflict, Americans n and south began to fear that the opposite section of the country had seized control of the government. By November 1860, an opponent of slavery's expansion arose from within the Republican Party. During the secession crunch that followed, fears nearly a century in the making at concluding devolved into encarmine war.

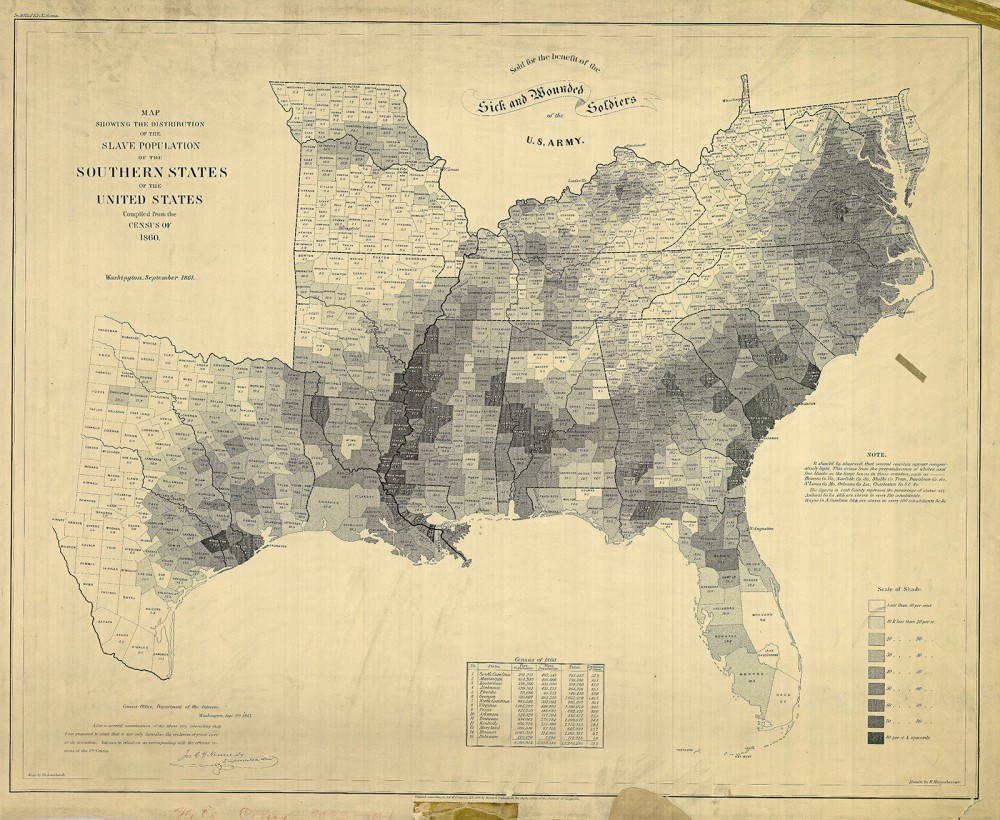

II. Sectionalism in the Early Democracy

This map, published by the US Coast Baby-sit, shows the percentage of enslaved people in the population in each county of the slave-holding states in 1860. The highest percentages lie along the Mississippi River, in the "Blackness Belt" of Alabama, and coastal S Carolina, all of which were centers of agricultural production (cotton and rice) in the United states. E. Hergesheimer (cartographer), Th. Leonhardt (engraver), Map Showing the Distribution of the Slave Population of the Southern States of the United States Compiled from the Census of 1860, c. 1861. Wikimedia.

Prior to the American Revolution, virtually everyone in the world accepted slavery equally a natural part of life.one English colonies northward and south relied on enslaved workers who grew tobacco, harvested indigo and carbohydrate, and worked in ports. They generated tremendous wealth for the British crown. That wealth and luxury fostered seemingly limitless opportunities and inspired seemingly boundless imaginations. Enslaved workers also helped give rise to revolutionary new ideals that in time became the ideological foundations of the sectional crisis. English language political theorists, in particular, began to rethink natural-constabulary justifications for slavery. They rejected the long-continuing idea that slavery was a condition that naturally suited some people. A new transatlantic antislavery move began to argue that liberty was the natural condition of humankind.two

Revolutionaries seized onto these ideas to stunning effect in the late eighteenth century. In the United States, France, and Haiti, revolutionaries began the work of splintering the sometime guild. Each revolution seemed to radicalize the next. Bolder and more expansive declarations of equality and freedom followed one afterwards the other. Revolutionaries in the Us alleged, "All men are created equal," in the 1770s. French visionaries issued the "Declaration of Rights and Man and Denizen" by 1789. But the about startling evolution came in 1803 in Republic of haiti. A revolution led by the isle's rebellious enslaved people turned France'south most valuable sugar colony into an independent country administered by the formerly enslaved.

The Haitian Revolution marked an early on origin of the sectional crisis. It helped splinter the Atlantic basin into clear zones of freedom and unfreedom, shattering the long-continuing assumption that African-descended enslaved people could not as well exist rulers. Despite the clear limitations of the American Revolution in attacking slavery, the era marked a powerful pause in slavery'south history. Military service on behalf of both the English and the American army freed thousands of enslaved people. Many others simply used the turmoil of war to make their escape. As a result, free Black communities emerged—communities that would continually reignite the antislavery struggle. For nigh a century, near white Americans were content to compromise over the outcome of slavery, merely the constant agitation of Black Americans, both enslaved and free, kept the issue alive.3

The national breakdown over slavery occurred over a long timeline and across a broad geography. Debates over slavery in the American West proved especially of import. Every bit the United States pressed west, new questions arose as to whether those lands ought to be slave or free. The framers of the Constitution did a trivial, but not much, to assistance resolve these early questions. Commodity 6 of the 1787 Northwest Ordinance banned slavery northward and westward of the Ohio River.4 Many took it to hateful that the founders intended for slavery to die out, as why else would they prohibit its spread across such a huge swath of territory?

Debates over the framers' intentions often led to confusion and bitter debate, merely the actions of the new government left better clues as to what the new nation intended for slavery. Congress authorized the admission of Vermont (1791) and Kentucky (1792), with Vermont coming into the Union as a costless state and Kentucky coming in as a slave state. Though Americans at the time made relatively lilliputian of the balancing human action suggested by the access of a slave state and a free state, the pattern became increasingly important, particularly when considering power in the United States Senate. By 1820, preserving the balance of free states and slave states would be seen as an issue of national security.

New pressures challenging the delicate balance again arose in the W. The Louisiana Purchase of 1803 more than doubled the size of the Us. Questions immediately arose as to whether these lands would exist made slave or gratuitous. Complicating matters farther was the rapid expansion of plantation slavery fueled by the invention of the cotton fiber gin in 1793. Even so even with the booming cotton economy, many Americans, including Thomas Jefferson, believed that slavery was a temporary establishment and would soon die out. Tensions rose with the Louisiana Purchase, simply a truly exclusive national argue remained mostly dormant.

That debate, yet, came quickly. Sectional differences tied to the expansion of plantation slavery in the Westward were especially important after 1803. The Ohio River Valley became an early on fault line in the coming sectional struggle. Kentucky and Tennessee emerged as slave states, while gratuitous states Ohio, Indiana (1816), and Illinois (1818) gained admission forth the river's northern banks. Borderland negotiations and accommodations forth the Ohio River fostered a distinctive kind of white supremacy, every bit laws tried to continue Black people out of the West entirely. Ohio's so-called Black Laws of 1803 foreshadowed the exclusionary cultures of Indiana, Illinois, and several subsequent states of the Former Northwest and later, the Far Westward.5 These laws often banned African American voting, denied Blackness Americans access to public schools, and made information technology impossible for nonwhites to serve on juries and in local militias, amid a host of other restrictions and obstacles.

The Missouri Territory, past far the largest section of the Louisiana Territory, marked a turning betoken in the sectional crisis. St. Louis, a humming Mississippi River boondocks filled with powerful enslavers, loomed large as an important merchandise headquarters for networks in the northern Mississippi Valley and the Greater West. In 1817, eager to put questions of whether this territory would be slave or gratuitous to balance, Congress opened its debate over Missouri's admission to the Marriage. Congressman James Tallmadge of New York proposed laws that would gradually cancel slavery in the new state. Southern states responded with unanimous outrage, and the nation shuddered at an undeniable exclusive controversy.vi

Congress reached a "compromise" on Missouri's admission, largely through the work of Kentuckian Henry Clay. Maine would be admitted to the Union as a free state. In exchange, Missouri would come into the Union as a slave country. Legislators sought to prevent time to come conflicts by making Missouri's southern border at 36°xxx′ the new dividing line between slavery and freedom in the Louisiana Purchase lands. South of that line, running east from Missouri to the western edge of the Louisiana Purchase lands (near the present-24-hour interval Texas panhandle), slavery could expand. N of information technology, encompassing what in 1820 was notwithstanding "unorganized territory," there would be no slavery.7

The Missouri Compromise marked a major turning point in America'south sectional crisis because it exposed to the public simply how divisive the slavery event had grown. The fence filled newspapers, speeches, and congressional records. Antislavery and pro-slavery positions from that betoken frontward repeatedly returned to points fabricated during the Missouri debates. Legislators battled for weeks over whether the Constitutional framers intended slavery'south expansion, and these contests left deep scars. Fifty-fifty seemingly simple and straightforward phrases like "all men are created equal" were hotly contested all over once again. Questions over the expansion of slavery remained open up, but about all Americans concluded that the Constitution protected slavery where information technology already existed.

Southerners were not all the same advancing arguments that said slavery was a positive good, but they did insist during the Missouri Debate that the framers supported slavery and wanted to see it expand. In Commodity I, Section ii, for example, the Constitution enabled representation in the South to exist based on rules defining an enslaved person equally 3-fifths of a voter, meaning southern white men would be overrepresented in Congress. The Constitution besides stipulated that Congress could not interfere with the slave trade before 1808 and enabled Congress to draft fugitive slave laws.

Antislavery participants in the Missouri debate argued that the framers never intended slavery to survive the Revolution and in fact hoped information technology would disappear through peaceful means. The framers of the Constitution never used the word slave. Enslaved people were referred to equally "persons held in service," perchance referring to English mutual law precedents that questioned the legitimacy of "property in man." Antislavery activists also pointed out that while Congress could non laissez passer a law limiting the slave trade earlier 1808, the framers had also recognized the flip side of the debate and had thus opened the door to legislating the slave trade's terminate once the borderline arrived. Language in the Tenth Amendment, they claimed, also said slavery could exist banned in the territories. Finally, they pointed to the due process clause of the Fifth Amendment, which said that holding could exist seized through appropriate legislation.eight The bruising Missouri debates ultimately transcended arguments about the Constitution. They became an extensive referendum on the American past, nowadays, and future.

Despite the furor, the Missouri crisis did non however inspire hardened defenses of either slave or complimentary labor. Those would come in the coming decades. In the concurrently, the uneasy consensus forged past the Missouri debate managed to bring a measure of at-home.

The Missouri debate had as well deeply troubled the nation'due south African Americans and Native Americans. By the fourth dimension of the Missouri Compromise debate, both groups saw that whites never intended them to be citizens of the U.s.a.. In fact, the debates over Missouri's admission had offered the first sustained debate on the question of Black citizenship, as Missouri's state constitution wanted to impose a hard ban on any future Black migrants. Legislators ultimately agreed that this hard ban violated the U.S. Constitution but reaffirmed Missouri'south ability to deny citizenship to African Americans. Americans by 1820 had endured a wide challenge, not merely to their cherished ideals simply also more than fundamentally to their conceptions of cocky.

III. The Crisis Joined

Missouri's admission to the Union in 1821 exposed deep fault lines in American social club. But the compromise created a new sectional consensus that most white Americans, at least, hoped would ensure a lasting peace. Through sustained debates and arguments, white Americans agreed that the Constitution could do little about slavery where information technology already existed and that slavery, with the State of Missouri as the fundamental exception, would never expand north of the 36°xxx′ line.

One time over again westward expansion challenged this consensus, and this time the results proved even more damaging. Tellingly, enslaved southerners were amid the first to betoken their discontent. A rebellion led by Denmark Vesey in 1822 threatened lives and property throughout the Carolinas. The nation's religious leaders as well expressed a ascent discontent with the new status quo.ix The 2d Neat Awakening farther sharpened political differences by promoting schisms within the major Protestant churches, schisms that too became increasingly sectional in nature. Betwixt 1820 and 1846, sectionalism drew on new political parties, new religious organizations, and new reform movements.

As politics grew more autonomous, leaders attacked old inequalities of wealth and power, but in doing so many pandered to a unity under white supremacy. Slavery briefly receded from the nation's attention in the early 1820s, but that would change quickly. By the final one-half of the decade, slavery was back, and this fourth dimension it appeared fifty-fifty more threatening.

Inspired by the social change of Jacksonian democracy, white men, regardless of status, would gain non only land and jobs but also the right to vote, the right to serve on juries, the right to nourish public schools, and the right to serve in the militia and armed forces. In this post-Missouri context, leaders arose to push the country's new expansionist desires in aggressive new directions. As they did so, however, the sectional crunch again deepened.

The Democratic Political party initially seemed to offer a compelling answer to the problems of sectionalism past promising benefits to white working men of the North, South, and West, while besides uniting rural, small-town, and urban residents. Indeed, huge numbers of western, southern, and northern workingmen rallied behind Andrew Jackson during the 1828 presidential election. The Democratic Political party tried to avoid the issue of slavery and instead sought to unite Americans around shared commitments to white supremacy and desires to aggrandize the nation.

Democrats were not without their critics. Northerners seen as especially friendly to the South had become known as "Doughfaces" during the Missouri debates, and as the 1830s wore on, more and more than Doughfaced Democrats became vulnerable to the charge that they served the southern slaving oligarchs better than they served their own northern communities. Whites discontented with the direction of the country used the slur and other critiques to help bit away at Democratic Party majorities. The accusation that northern Democrats were lapdogs for southern enslavers had real power.ten

The Whigs offered an organized major-political party challenge to the Democrats. Whig strongholds often mirrored the patterns of due west migrations out of New England. Whigs drew from an odd coalition of wealthy merchants, middle- and upper-class farmers, planters in the Upland Due south, and settlers in the Smashing Lakes. Because of this motley coalition, the political party struggled to bring a cohesive message to voters in the 1830s. Their strongest support came from places like Ohio'due south Western Reserve, the rural and Protestant-dominated areas of Michigan, and similar parts of Protestant and modest-town Illinois, particularly the fast-growing towns and cities of the state'due south northern half.11

Whig leaders stressed Protestant civilization and federal-sponsored internal improvements and courted the support of a multifariousness of reform movements, including temperance, nativism, and fifty-fifty antislavery, though few Whigs believed in racial equality. These positions attracted a wide range of figures, including a young convert to politics named Abraham Lincoln. Lincoln admired Whig leader Henry Dirt of Kentucky, and by the early 1830s, Lincoln certainly fit the paradigm of a developing Whig. A veteran of the Black Hawk War, Lincoln had relocated to New Salem, Illinois, where he worked a variety of odd jobs, living a life of thrift, self-discipline, and sobriety as he educated himself in preparation for a professional life in law and politics.

The Whig Party blamed Democrats for defending slavery at the expense of the American people, simply antislavery was never a core component of the Whig platform. Several abolitionists grew so disgusted with the Whigs that they formed their own party, a true antislavery party. Activists in Warsaw, New York, organized the antislavery Freedom Political party in 1839. Liberty leaders demanded the end of slavery in the District of Columbia, the end of the interstate slave trade, and the prohibition of slavery's expansion into the West. But the Liberty Political party as well shunned women'south participation in the movement and distanced themselves from visions of true racial egalitarianism. Few Americans voted for the political party. The Democrats and Whigs continued to boss American politics.

Democrats and Whigs fostered a moment of relative calm on the slavery contend, partially aided by gag rules prohibiting discussion of antislavery petitions. Arkansas (1836) and Michigan (1837) became the newest states admitted to the Wedlock, with Arkansas coming in as a slave land, and Michigan coming in as a free state. Michigan gained admission through provisions established in the Northwest Ordinance, while Arkansas came in under the Missouri Compromise. Since its lands were beneath the line at 36°thirty′, the access of Arkansas did not threaten the Missouri consensus. The balancing human activity between slavery and freedom continued.

Events in Texas would shatter the remainder. Contained Texas soon gained recognition from a supportive Andrew Jackson assistants in 1837. But Jackson's successor, President Martin Van Buren, as well a Democrat, soon had reasons to worry nigh the Republic of Texas. Texas struggled with ongoing conflicts with Mexico and raids from the powerful Comanche. The 1844 democratic presidential candidate James One thousand. Polk sought to bridge the sectional divide by promising new lands to whites northward and south. Polk cited the annexation of Texas and the Oregon Territory as campaign cornerstones.12 Nonetheless as Polk championed the acquisition of these vast new lands, northern Democrats grew annoyed by their southern colleagues, particularly when it came to Texas.

For many observers, the debates over Texas statehood illustrated that the federal government was clearly pro-slavery. Texas president Sam Houston managed to secure a bargain with Polk and gained admission to the Wedlock for Texas in 1845. Antislavery northerners besides worried near the admission of Florida, which entered the Wedlock as a slave country in 1845. The yr 1845 became a pivotal year in the retention of antislavery leaders. As Americans embraced calls to pursue their manifest destiny, antislavery voices looked at developments in Florida and Texas as signs that the sectional crunch had taken an ominous and perchance irredeemable plow.

The 1840s opened with a number of agonizing developments for antislavery leaders. The 1842 Supreme Court example Prigg five. Pennsylvania ruled that the federal authorities's Fugitive Slave Act trumped Pennsylvania's personal freedom police force.xiii Antislavery activists believed that the federal authorities just served southern enslavers and were trouncing united states' rights of the North. A number of northern states reacted by passing new personal liberty laws in protestation in 1843.

The ascension controversy over the status of liberty-seeking people swelled partly through the influence of escaped formerly enslaved people, including Frederick Douglass. Douglass'south entrance into northern politics marked an of import new development in the nation's coming exclusive crisis. Born into slavery in 1818 at Talbot County, Maryland, Douglass grew up, similar many enslaved people, barely having known his own female parent or date of nativity. And yet because of a range of unique privileges afforded him by the circumstances of his upbringing, likewise as his own genius and decision, Douglass managed to learn how to read and write. He used these skills to escape from slavery in 1837, when he was but nineteen. Past 1845, Douglass put the finishing touches on his autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass.14 The book launched his lifelong career every bit an advocate for the enslaved and helped further raise the visibility of Black politics. Other formerly enslaved people, including Sojourner Truth, joined Douglass in rousing support for antislavery, as did free Blackness Americans like Maria Stewart, James McCune Smith, Martin Delaney, and numerous others.15 Just Black activists did more than deliver speeches. They likewise attacked fugitive slave laws past helping thousands to escape. The incredible career of Harriet Tubman is one of the more dramatic examples. But the forces of slavery had powerful allies at every level of authorities.

The yr 1846 signaled new reversals to the antislavery cause and the ancestry of a nighttime new era in American politics. President Polk and his Democratic allies were eager to see western lands brought into the Matrimony and were especially anxious to see the borders of the nation extended to the shores of the Pacific Bounding main. Critics of the administration blasted these efforts every bit piffling more than than land grabs on behalf of enslavers. Events in early 1846 seemed to justify antislavery complaints. Since United mexican states had never recognized independent Texas, information technology continued to lay claim to its lands, even later on the United States admitted information technology to the Union. In January 1846, Polk ordered troops to Texas to enforce claims stemming from its border dispute forth the Rio Grande. Polk asked for state of war on May 11, 1846, and by September 1847, the United States had invaded United mexican states City. Whigs, like Abraham Lincoln, found their protests sidelined, but antislavery voices were becoming more vocal and more powerful.

After 1846, the exclusive crisis raged throughout North America. Debates swirled over whether the new lands would be slave or free. The South began defending slavery as a positive good. At the aforementioned time, Congressman David Wilmot submitted his Wilmot Proviso late in 1846, banning the expansion of slavery into the territories won from Mexico. The proviso gained widespread northern support and even passed the Firm with bipartisan support, merely it failed in the Senate.

IV. Gratuitous Soil, Complimentary Labor, Free Men

The conclusion of the Mexican War led to the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. The treaty infuriated antislavery leaders in the United States. The spoils of war were impressive, but information technology was clear they would help expand slavery. Antislavery activists, who already judged the Mexican War an enslavers' plot, vowed that no new territories would be opened to slavery. Only knowing that the Liberty Party was also not probable to provide a home to many moderate voters, leaders fostered a new and more competitive party, which they called the Costless Soil Party. Antislavery leaders had thought that their vision of a federal government divorced from slavery might be represented by the major parties in that year's presidential election, simply both the Whigs and the Democrats nominated candidates hostile to the antislavery cause. Left unrepresented, antislavery Gratuitous Soil leaders swung into activeness.

Questions about the residue of free and slave states in the Union became even more fierce after the Us acquired these territories from Mexico past the 1848 in the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. Map of the Mexican Cession, 2008. Wikimedia.

Demanding an alternative to the pro-slavery status quo, Free Soil leaders assembled and so-chosen Censor Whigs. The new coalition called for a national convention in August 1848 at Buffalo, New York. A number of ex-Democrats committed to the party correct away, including an important group of New Yorkers loyal to Martin Van Buren. The Gratuitous Soil Party'due south platform bridged the eastern and western leadership together and chosen for an end to slavery in Washington, D.C., and a halt on slavery'due south expansion in the territories.sixteen The Free Soil movement hardly made a paring in the 1848 presidential election, but it drew more than than four times the popular vote won by the Liberty Party earlier. It was a promising get-go. In 1848, Gratuitous Soil leaders claimed merely 10 per centum of the pop vote but won over a dozen House seats and fifty-fifty managed to win ane Senate seat in Ohio, which went to Salmon P. Chase.17 In Congress, Free Soil members had enough votes to swing power to either the Whigs or the Democrats.

The admission of Wisconsin as a free land in May 1848 helped cool tensions subsequently the Texas and Florida admissions. Meanwhile, news from a number of failed European revolutions alarmed American reformers, only every bit exiled radicals filtered into the United States, a strengthening women'due south rights movement likewise flexed its muscle at Seneca Falls, New York. Led by figures such every bit Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott, women with deep ties to the abolitionist crusade, it represented the first of such meetings always held in U.Due south. history.18 Frederick Douglass also appeared at the convention and took part in the proceedings, where participants debated the Declaration of Sentiments, Grievances, and Resolutions.19 Past August 1848, it seemed plausible that the Free Soil Move might tap into these reforms and build a broader coalition. In some means that is precisely what information technology did. But come up November, the spirit of reform failed to yield much at the polls. Whig candidate Zachary Taylor bested Democrat Lewis Cass of Michigan.

The upheavals of 1848 came to a quick cease. Taylor remained in office only a brief time until his unexpected decease from a stomach disquiet in 1850. During Taylor's brief time in office, the fruits of the Mexican War began to spoil. While Taylor was alive, his administration struggled to detect a skillful remedy. Increased clamoring for the access of California, New Mexico, and Utah pushed the country closer to the edge. Gold had been discovered in California, and as thousands continued to pour onto the West Coast and through the trans-Mississippi West, the admission of new states loomed. In Utah, Mormons were also making claims to an independent state they called Deseret. By 1850, California wanted admission as a free country. With so many competing dynamics nether mode, and with the president expressionless and replaced past Whig Millard Fillmore, the 1850s were off to a troubling start.

Congressional leaders like Henry Clay and newer legislators like Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois were asked to broker a compromise, but this time it was articulate no compromise could span all the diverging interests at play in the country. Clay eventually left Washington disheartened by diplomacy. It savage to immature Stephen Douglas, and so, to shepherd the bills through Congress, which he in fact did. Legislators rallied backside the Compromise of 1850, an assemblage of bills passed late in 1850, which managed to keep the promises of the Missouri Compromise alive.

Henry Dirt ("The Great Compromiser") addresses the U.S. Senate during the debates over the Compromise of 1850. The print shows a number of incendiary personalities, like John C. Calhoun, whose increasingly sectional beliefs were pacified for a time by the Compromise. P. F. Rothermel (creative person), c. 1855. Wikimedia.

The Compromise of 1850 tried to offer something to anybody, but in the stop it but worsened the sectional crisis. For southerners, the parcel offered a tough new fugitive slave constabulary that empowered the federal government to deputize regular citizens in arresting runaways. The New Mexico Territory and the Utah Territory would be immune to determine their own fates as slave or free states based on popular sovereignty. The compromise also allowed territories to submit suits directly to the Supreme Courtroom over the status of freedom-seeking people inside their bounds.

The admission of California every bit the newest free state in the Union cheered many northerners, merely fifty-fifty the admission of a vast new state full of resources and rich agricultural lands was not enough. In addition to California, northerners also gained a ban on the slave trade in Washington, D.C., but not the full emancipation abolitionists had long advocated. Texas, which had already come into the Marriage as a slave country, was asked to give some of its state to New Mexico in render for the federal government absorbing some of the old republic'southward debt. Only the compromise debates soon grew ugly.

After the Compromise of 1850, antislavery critics became increasingly certain that enslavers had co-opted the federal government, and that a southern Slave Power secretly held sway in Washington, where it hoped to make slavery a national institution. These northern complaints pointed back to how the iii-fifths compromise of the Constitution gave southerners proportionally more representatives in Congress. In the 1850s, antislavery leaders increasingly argued that Washington worked on behalf of enslavers while ignoring the interests of white working men.

None of the individual measures in the Compromise of 1850 proved more troubling to antislavery Americans than the Fugitive Slave Act. In a clear bid to extend slavery's influence throughout the country, the act created special federal commissioners to decide the fate of declared fugitives without benefit of a jury trial or even court testimony. Under its provisions, local regime in the Northward could not interfere with the capture of fugitives. Northern citizens, moreover, had to assist in the abort of fugitives when called upon past federal agents. The Avoiding Slave Deed created the foundation for a massive expansion of federal power, including an alarming increase in the nation's policing powers. Many northerners were also troubled past the fashion the pecker undermined local and state laws. The law itself fostered corruption and the enslavement of costless Black northerners. The federal commissioners who heard these cases were paid $x if they determined that the defendant was enslaved and merely $5 if they determined he or she was free.20 Many Blackness northerners responded to the new police force by heading farther north to Canada.

The 1852 presidential election gave the Whigs their most stunning defeat and effectively ended their beingness every bit a national political political party. Whigs captured just 42 of the 254 electoral votes needed to win. With the Compromise of 1850 and plenty of new lands, peaceful consensus seemed to be on the horizon. Antislavery feelings continued to run deep, notwithstanding, and their depth revealed that with a Autonomous Party misstep, a coalition united confronting the Democrats might yet sally and bring them to defeat. Ane measure out of the popularity of antislavery ideas came in 1852 when Harriet Beecher Stowe published her best-selling antislavery novel, Uncle Tom'south Cabin. Sales for Uncle Tom's Cabin were astronomical, eclipsed merely by sales of the Bible.21 The book became a sensation and helped move antislavery into everyday chat for many northerners. Despite the powerful antislavery bulletin, Stowe'due south book likewise reinforced many racist stereotypes. Fifty-fifty abolitionists struggled with the securely ingrained racism that plagued American society. While the major success of Uncle Tom's Cabin bolstered the abolitionist crusade, the terms outlined by the Compromise of 1850 appeared strong plenty to go on the peace.

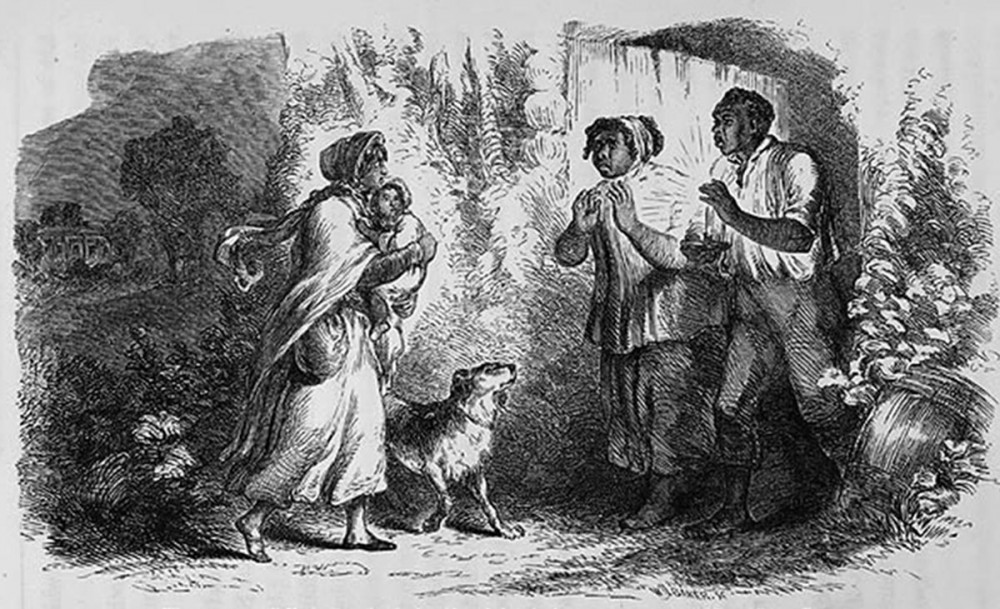

Uncle Tom'south Cabin intensified an already hot argue over slavery throughout the Usa. The book revolves around Eliza (the woman holding the young boy) and Tom (standing with his married woman Chloe), each of whom takes a very dissimilar path: Eliza escapes slavery using her ain two feet, but Tom endures his chains but to die past the whip of a brutish enslaver. The horrific violence that both endured melted the hearts of many northerners and pressed some to bring together in the fight against slavery. Full-page illustration by Hammatt Billings for Uncle Tom's Cabin, 1852. Wikimedia.

Democrats by 1853 were badly splintered along sectional lines over slavery, but they also had reasons to act with confidence. Voters had returned them to role in 1852 following the bitter fights over the Compromise of 1850. Emboldened, Illinois senator Stephen A. Douglas introduced a set of additional amendments to a bill drafted in late 1853 to help organize the Nebraska Territory, the concluding of the Louisiana Purchase lands. In 1853, the Nebraska Territory was huge, extending from the northern end of Texas to the Canadian border. Birthday, it encompassed present-day Nebraska, Wyoming, South Dakota, Due north Dakota, Colorado, and Montana. Douglas's efforts to amend and introduce the pecker in 1854 opened dynamics that would pause the Democratic Party in 2 and, in the process, rip the country autonomously.

Douglas proposed a bold programme in 1854 to cut off a big southern clamper of Nebraska and create it separately as the Kansas Territory. Douglas had a number of goals in mind. The expansionist Democrat from Illinois wanted to organize the territory to facilitate the completion of a national railroad that would flow through Chicago. Merely earlier he had even finished introducing the bill, opposition had already mobilized. Salmon P. Chase drafted a response in northern newspapers that exposed the Kansas-Nebraska Bill as a measure to overturn the Missouri Compromise and open western lands for slavery. Kansas-Nebraska protests emerged in 1854 throughout the North, with key meetings in Wisconsin and Michigan. Kansas would get slave or free depending on the result of local elections, elections that would be greatly influenced by migrants flooding to the state to either protect or finish the spread of slavery.

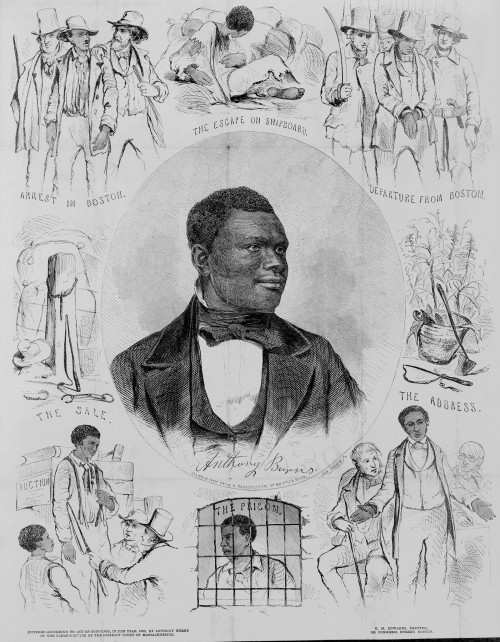

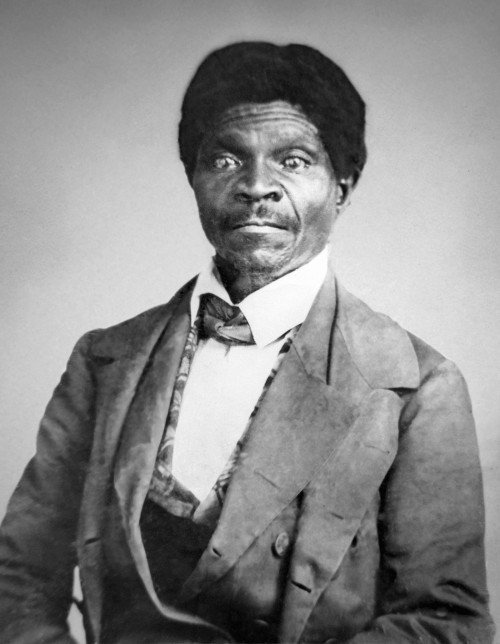

Ordinary Americans in the North increasingly resisted what they believed to be a pro-slavery federal government on their own terms. The rescues and arrests of enslaved men similar Anthony Burns in Boston and Joshua Glover in Milwaukee signaled the rising vehemence of resistance to the nation'due south 1850 fugitive slave law. The case of Anthony Burns illustrates how the Fugitive Slave Law radicalized many northerners. On May 24, 1854, twenty-year-old Burns, a preacher who worked in a Boston article of clothing shop, was clubbed and dragged to jail. One yr before, Burns had escaped slavery in Virginia, and a group of slave catchers had come to return him to Richmond. Word of Burns'due south capture spread quickly through Boston, and a mob gathered outside the courthouse demanding Burns's release. Two days later the arrest, the crowd stormed the courthouse and shot a deputy U.Southward. Marshal to death. News reached Washington, and the federal authorities sent soldiers. Boston was placed under martial police force. Federal troops lined the streets of Boston as Burns was marched to a send, where he was sent back to slavery in Virginia. After spending over $40,000, the U.S. regime had successfully reenslaved Anthony Burns.22 A short time later, Burns was redeemed past abolitionists who paid $1,300 to return him to freedom, simply the outrage amongst Bostonians only grew. And Anthony Burns was only ane of hundreds of highly publicized episodes of the federal government imposing the Fugitive Slave Law on rebellious northern populations. In the words of Amos Adams Lawrence, "We went to bed one night onetime-fashioned, conservative, compromise Matrimony Whigs & woke upwards stark mad Abolitionists."23

Anthony Burns, the avoiding slave, appears in a portrait at the center of this 1855 print. Burns' abort and trial, possible because of the 1850 Avoiding Slave Act, became a rallying cry. As a symbol of the injustice of the slave system, Burns' treatment spurred riots and protests by abolitionists and citizens of Boston in the spring of 1854. John Andrews (engraver), "Anthony Burns," c. 1855. Library of Congress.

As northerners radicalized, organizations like the New England Emigrant Aid Company provided guns and other goods for pioneers willing to go to Kansas and establish the territory as antislavery through popular sovereignty. On all sides of the slavery issue, politics became increasingly militarized.

The year 1855 nearly derailed the northern antislavery coalition. A resurgent anti-immigrant movement briefly took advantage of the Whig collapse and near stole the energy of the anti-administration forces by channeling its frustrations into fights confronting the large number of mostly Catholic High german and Irish immigrants in American cities. Calling themselves Know-Nothings, on account of their tendency to pretend ignorance when asked about their activities, the Know-Nothing or American Political party made impressive gains in 1854 and 1855, particularly in New England and the Middle Atlantic. Just the anti-immigrant move simply could not capture the nation'due south attention in ways the antislavery movement already had.24

The antislavery political movements that started in 1854 coalesced with the formation of a new political party. Harking back to the founding fathers, its organizers named it the Republican Party. Republicans moved forward into a highly charged summer.

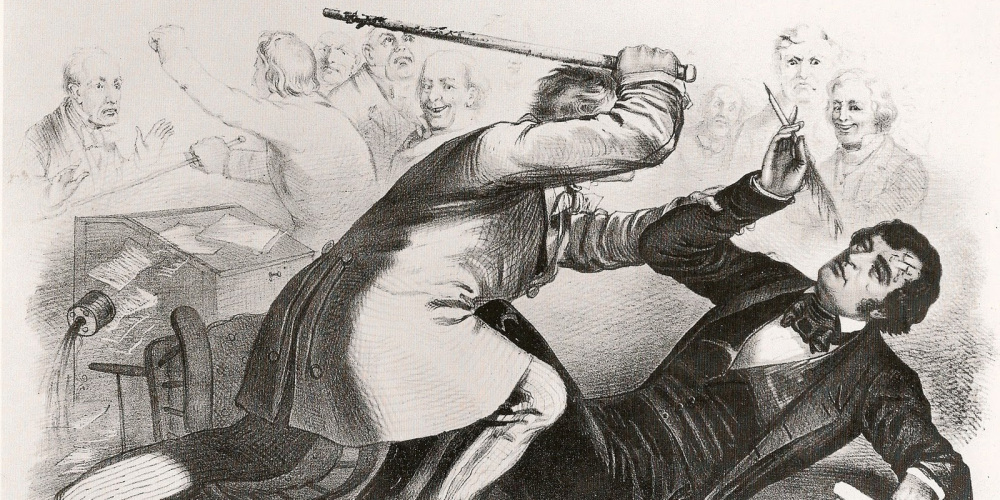

Following an explosive speech before Congress on May 19–twenty, Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts was violently browbeaten with a pikestaff by Representative Preston Brooks of South Carolina on the floor of the Senate sleeping room. Among other accusations, Sumner accused Senator Andrew Butler of South Carolina, Brooks's cousin, of defending slavery then he could have sexual access to Blackness women.25 Brooks felt that he had to defend his relative'southward accolade and most killed Sumner every bit a event.

The Caning of Charles Sumner, 1856. Wikimedia.

The violence in Washington pales before the many murders occurring in Kansas.26 Pro-slavery raiders attacked Lawrence, Kansas. Radical abolitionist John Brown retaliated, murdering several pro-slavery Kansans in retribution. Equally all of this played out, the House failed to expel Brooks. Brooks resigned his seat anyway, only to be reelected by his constituents after in the year. He received new canes emblazoned with the words "Hit him once again!"27

With sectional tensions at a breaking point, both parties readied for the coming presidential ballot. In June 1856, the newly named Republican Party held its nominating convention at Philadelphia and selected Californian John Charles Frémont. Frémont's antislavery credentials may not have pleased many abolitionists, only his dynamic and talented wife, Jessie Benton Frémont, appealed to more than radical members of the coalition. The Kansas-Nebraska argue, the organization of the Republican Political party, and the 1856 presidential campaign all energized a new generation of political leaders, including Abraham Lincoln. Beginning with his speech at Peoria, Illinois, in 1854, Lincoln carved out a bulletin that encapsulated amend than anyone else the principal ideas and visions of the Republican Party.28 Lincoln himself was slow to join the coalition, notwithstanding by the summer of 1856, Lincoln had fully committed to the Frémont campaign.

Frémont lost, but Republicans celebrated that he won eleven of the xvi free states. This showing, they urged, was truly impressive for any party making its first run at the presidency. Withal northern Democrats in crucial swing states remained unmoved by the Republican Political party's appeals. Ulysses Southward. Grant of Missouri, for instance, worried that Frémont and Republicans signaled trouble for the Union itself. Grant voted for the Democratic candidate, James Buchanan, believing a Republican victory might bring nigh disunion. In abolitionist and especially Black American circles, Frémont'southward defeat was more than a disappointment. Believing their fate had been sealed as permanent noncitizens, some African Americans would consider foreign emigration and colonization. Others began to explore the selection of more than radical and straight action against the Slave Ability.

V. From Sectional Crisis to National Crisis

White antislavery leaders hailed Frémont'southward defeat as a "glorious" one and looked ahead to the political party'south future successes. For those still in slavery or hoping to see loved ones freed, the news was of course much harder to take. The Republican Party had promised the rising of an antislavery coalition, just voters rebuked it. The lessons seemed clear enough.

Kansas loomed large over the 1856 election, darkening the national mood. The story of voter fraud in Kansas had begun years earlier in 1854, when nearby Missourians first started crossing the border to tamper with the Kansas elections. Noting this, critics at the time attacked the Pierce assistants for not living upwards to the ideals of popular sovereignty by ensuring off-white elections. From at that place, the crisis only deepened. Kansas voted to come into the Union as a free state, but the federal government refused to recognize their votes and instead recognized a sham pro-slavery legislature.

The sectional crisis had at last become a national crisis. "Bleeding Kansas" was the first place to demonstrate that the sectional crisis could easily be, and in fact already was, exploding into a full-blown national crisis. As the national mood grew increasingly grim, Kansas attracted militants representing the extreme sides of the slavery argue.

In the days subsequently the 1856 presidential election, Buchanan fabricated his plans for his time in part clear. He talked with Principal Justice Roger Taney on inauguration 24-hour interval well-nigh a courtroom decision he hoped to run across handled during his time in office. Indeed, not long after the inauguration, the Supreme Court handed down a conclusion that would come to ascertain Buchanan's presidency. The Dred Scott decision, Scott v. Sandford, ruled that Blackness Americans could not be citizens of the United States.29 This gave the Buchanan administration and its southern allies a direct repudiation of the Missouri Compromise. The courtroom ruled that Scott, a Missouri slave, had no correct to sue in United states courts. The Dred Scott conclusion signaled that the federal government was now fully committed to extending slavery as far and as wide equally information technology might want.

Dred Scott'southward Supreme Court example made clear that the federal authorities was no longer able or willing to ignore the issue of slavery. More than than that, all Black Americans, Justice Taney declared, could never be citizens of the United States. Though seemingly a disastrous determination for abolitionists, this controversial ruling actually increased the ranks of the abolitionist motility. Photo of Dred Scott, 1857. Wikimedia.

The Dred Scott decision seemed to settle the exclusive crisis by making slavery fully national, merely in reality it just exacerbated sectional tensions further. In 1857, Buchanan sent U.S. military forces to Utah, hoping to subdue Utah's Mormon communities. This action, however, led to renewed charges, many of them leveled from inside his own party, that the administration was abusing its powers. Far more important than the Utah invasion, however, were the ongoing events in Kansas. It was Kansas that at final proved to many northerners that the sectional crunch would not go away unless slavery also went away.

The Illinois Senate race in 1858 put the scope of the exclusive crunch on full display. Republican candidate Abraham Lincoln challenged the greatly influential Democrat Stephen Douglas. Pandering to appeals to white supremacy, Douglas hammered the Republican opposition as a "Blackness Republican" party aptitude on racial equality.30 The Republicans, including Lincoln, were thrown on the defensive. Democrats hung on as best they could, but the Republicans won the House of Representatives and picked up seats in the Senate. Lincoln really lost his contest with Stephen Douglas but in the process firmly established himself as a leading national Republican. After the 1858 elections, all optics turned to 1860. Given the Republican Political party'southward successes since 1854, it was expected that the 1860 presidential election might produce the nation's offset antislavery president.

In the troubled decades since the Missouri Compromise, the nation slowly tore itself apart. Congressmen clubbed each other nearly to death on the flooring of Congress, and past the middle of the 1850s Americans were already at war on the Kansas and Missouri plains. Beyond the state, cities and towns were in various stages of revolt against federal authorisation. Fighting spread fifty-fifty farther against Native Americans in the Far West and against Mormons in Utah. The nation's militants anticipated a coming breakup and worked to exploit it. John Brown, fresh from his deportment in Kansas, moved east and planned more than violence. Assembling a team from across the W, including Black radicals from Oberlin, Ohio, and throughout communities in western Canada, Dark-brown hatched a plan to attack Harper's Ferry, a federal weapons arsenal in Virginia (now West Virginia). He would use the weapons to lead a defection of enslaved people. Brown approached Frederick Douglass, though Douglass refused to join.

Brown'south raid embarked on Oct 16. Past October 18, a command under Robert E. Lee had crushed the revolt. Many of Dark-brown'due south men, including his own sons, were killed, but Brown himself lived and was imprisoned. Brown prophesied while in prison house that the nation's crimes would only exist purged with blood. He went to the gallows in December 1859. Northerners fabricated a stunning display of sympathy on the day of his execution. Southerners took their reactions to mean that the coming 1860 election would be, in many ways, a referendum on secession and disunion.

The execution of John Brown made him a martyr in abolitionist circles and a confirmed traitor in southern crowds. Both of these images continued to pervade public memory later the Civil War, but in the North especially (where so many soldiers had died to aid cease slavery) his name was admired. Over two decades later on Brown'south death, Thomas Hovenden portrayed Brown equally a saint. As he is lead to his execution for attempting to destroy slavery, Dark-brown poignantly leans over a rail to kiss a Blackness baby. Thomas Hovenden, The Concluding Moments of John Brown, c. 1882-1884. Wikimedia.

Republicans wanted trivial to do with Brown and instead tried to portray themselves as moderates opposed to both abolitionists and pro-slavery expansionists. In this climate, the parties opened their contest for the 1860 presidential ballot. The Democratic Political party fared poorly equally its southern delegates bolted its national convention at Charleston and ran their own candidate, Vice President John C. Breckenridge of Kentucky. Hoping to field a candidate who might nonetheless manage to bridge the broken party's factions, the Democrats decided to meet again at Baltimore and nominated Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois.

The Republicans, meanwhile, held their bouncy convention in Chicago. The Republican platform made the party's antislavery commitments clear, besides making wide promises to its white constituents, particularly westerners, with the hope of new state, transcontinental railroads, and broad support of public schools.31 Abraham Lincoln, a candidate few outside Illinois truly expected to win, still proved far less polarizing than the other names on the ballot. Lincoln won the nomination, and with the Democrats in disarray, Republicans knew their candidate Lincoln had a good chance of winning.

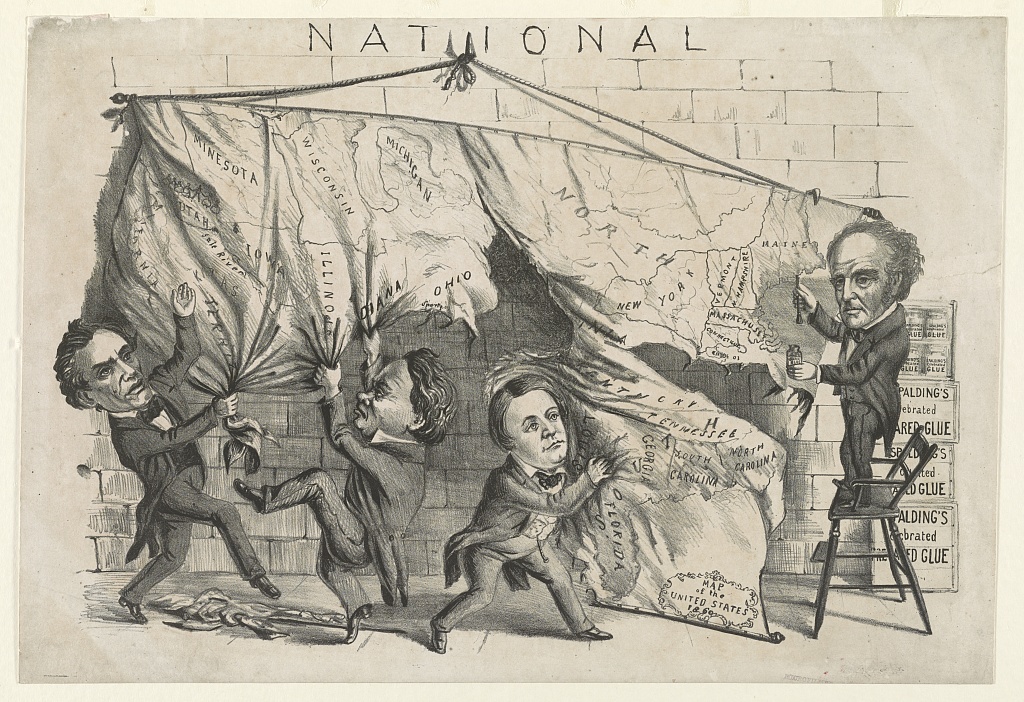

This political cartoon depicts the four candidates in the 1860 presidential election. Dividing the National Map. Available from the Library of Congress.

Abraham Lincoln won the 1860 competition on Nov 6, gaining just 40 percentage of the pop vote and non a single southern vote in the Electoral College. Within days, southern states were organizing secession conventions. John J. Crittenden of Kentucky proposed a series of compromises, but a clear pro-southern bias meant they had little risk of gaining Republican acceptance. Crittenden's plan promised renewed enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Law and offered a plan to keep slavery in the nation'southward capital letter.32 Republicans past late 1860 knew that the voters who had just placed them in power did non want them to cave on these points, and southern states proceeded with their plans to exit the Marriage. On Dec 20, S Carolina voted to secede and issued its Declaration of the Immediate Causes."33 The proclamation highlighted failure of the federal government to enforce the Fugitive Slave Human activity over competing personal freedom laws in northern states. After the war many southerners claimed that secession was primarily motivated by a business concern to preserve states' rights, only the primary complaint of the very start ordinance of secession listed the federal government'southward failure to exert its say-so over the northern states.

The twelvemonth 1861, and then, saw the culmination of the secession crunch. Before he left for Washington, Lincoln told those who had gathered in Springfield to wish him well and that he faced a "task greater than Washington's" in the years to come up. Southerners were besides learning the challenges of forming a new nation. The seceded states grappled with internal divisions correct abroad, equally states with enslavers sometimes did not support the newly seceded states. In January, for instance, Delaware rejected secession. Just states in the Lower South adopted a different course. The state of Mississippi seceded. Later in the calendar month, u.s. of Florida, Alabama, Georgia, and Louisiana also all left the Union. By early February, Texas had as well joined the newly seceded states. In February, southerners drafted a constitution protecting slavery and named Jefferson Davis of Mississippi their president. Weeks after Abraham Lincoln's inauguration, rebels in the newly formed Confederate States of America opened fire on Fort Sumter in Southward Carolina. Within days, Abraham Lincoln would demand lxx-five m volunteers from the North to beat out the rebellion. The American Civil State of war had begun.

6. Determination

Slavery had long divided the politics of the Us. In time, these divisions became both exclusive and irreconcilable. The starting time and virtually ominous sign of a coming sectional storm occurred over debates surrounding the admission of the state of Missouri in 1821. As westward expansion connected, these fault lines grew even more ominous, particularly equally the United states managed to seize even more lands from its state of war with United mexican states. The country seemed to teeter ever closer to a total-throated endorsement of slavery. But an antislavery coalition arose in the middle 1850s calling itself the Republican Party. Eager to cordon off slavery and confine it to where it already existed, the Republicans won the presidential election of 1860 and threw the nation on the path to war.

Throughout this flow, the mainstream of the antislavery motion remained committed to a peaceful resolution of the slavery issue through efforts understood to foster the "ultimate extinction" of slavery in due fourth dimension. But as the secession crunch revealed, the South could not tolerate a federal authorities working against the interests of slavery's expansion and decided to take a gamble on state of war with the Us. Secession, in the end, raised the possibility of emancipation through state of war, a possibility most Republicans knew, of form, had always been an option, but i they nevertheless hoped would never be necessary. Past 1861 all bets were off, and the fate of slavery, and of the nation, depended on war.

Vii. Primary Sources

1. Prigg v. Pennsylvania, 1842

Conflicts between the power of the federal regime and states' rights strained American politics throughout the antebellum era. During the 1840s and 1850s, the near consistent source of tension on the issue stemmed from northerners refusing to comply with fugitive slave laws. As early every bit the 1780s, Pennsylvania passed laws that made it illegal to have a Blackness person from the state for the purpose of enslaving them. In the majority opinion, excerpted here, Supreme Court justice Joseph Story decided that the national fugitive slave act overruled Pennsylvania'south constabulary.

ii. Stories from the Hush-hush Railroad, 1855-56

William Still was an African-American abolitionist who ofttimes risked his life to help freedom-seekers escape slavery. In these excerpts, Withal offers the readers some of the letters sent to him from abolitionists and formerly enslaved persons. The passages shed calorie-free on family separation, the financial costs of the journey to liberty, and the logistics of the Hole-and-corner Railroad.

3. Harriet Beecher Stowe,Uncle Tom's Cabin, 1852

In 1852 Harriet Beecher Stowe published her bestselling antislavery novel,Uncle Tom's Cabin. Sales forUncle Tom's Cabin were astronomical, eclipsed only by sales of the Bible. The volume became a sensation and helped move antislavery into everyday conversation for many northerners. In this passage, a senator and his wife argue the Fugitive Slave Police force.

iv. Charlotte Forten complains of racism in the North, 1855

Writer, activist, and teacher Charlotte Forten was built-in in Philadelphia in 1837 to a well-to-do African American family. Forten's diary entries from 1854 illuminate sectional tensions, especially in her discussion of the trial of Anthony Burns, a avoiding from slavery. She likewise expressed frequent frustration over the racism she encountered in Boston.

five. Margaraetta Mason and Lydia Maria Child talk over John Brown, 1860

After John Brown was arrested for his raid on Harpers Ferry, Lydia Maria Child wrote to the governor of Virginia requesting to visit Brown. Margaretta Stonemason of Virginia wrote a searing letter to Child attacking her for supporting a murder. Child responded, and the substitution of letters was published by the American Antislavery Society.

half dozen. 1860 Republican Political party platform

The 1860 Republican Political party convention in Chicago created a platform that clearly opposed the expansion of slavery in the West and the reopening of the slave trade. However, cypher in the certificate claimed that the government had the ability to eliminate slavery where information technology already existed. Controversies over slavery suffuse the platform, but maybe even more noticeable is the importance of the W to the Republican Party.

7. South Carolina announcement of secession, 1860

Abraham Lincoln won the 1860 contest on November 6 with just xl% of the pop vote and not a single southern vote in the Electoral College. Within days, southern states were organizing secession conventions. On December twenty, South Carolina voted to secede, and issued its "Declaration of the Firsthand Causes."

viii. Effects of the Fugitive Slave Law lithograph, 1850

This lithograph imagines the consequences of the Fugitive Slave Deed, part of the Compromise of 1850. Four well-dressed Black men are being hunted past a political party of white men, seen in the background. In that location are a number of ambiguities in the image – are the Blackness men enslaved or gratis? Are they trying to escape or non? Where exactly are they? These ambiguities speak to the concerns many abolitionists had almost the police force, which required gratuitous citizens to return freedom-seeking people to their enslavers.

9. Sectional crunch map, 1856

This piece of Republican propaganda from the 1856 election makes clear distinctions between gratuitous states, slave states, and territories. Featured at the top of the page are engravings of John C. Fremont and his running mate, William C. Dayton. A vibrant red sets off the free states. The chart, "Freedom vs. Slavery," demonstrates the North's economical and cultural superiority over slave states in terms of everything from population per square mile, capital in articles, miles of railroad, the number of newspapers and public libraries, and value of churches.

8. Reference Material

This chapter was edited by Jesse Gant, with content contributions by Jeffrey Bain-Conkin, Matthew A. Byron, Christopher Childers, Jesse Gant, Christopher Null, Ryan Poe, Michael Robinson, Nicholas Wood, Michael Forest, and Ben Wright.

Recommended commendation: Jeffrey Bain-Conkin et al., "The Sectional Crisis," Jesse Gant, ed., in The American Yawp, eds. Joseph Locke and Ben Wright (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2018).

Recommended Reading

- Bacon, Margaret Promise. Merely One Race: The Life of Robert Purvis. Albany: SUNY Press, 2012.

- Baker, Jean H. Affairs of Party: The Political Culture of Northern Democrats in the Mid-Nineteenth Century. New York: Fordham University Printing, 1983.

- Berlin, Ira. Generations of Captivity: A History of African-American Slaves. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 2003.

- Boydston, Jeanne. Dwelling house and Work: Housework, Wages, and the Ideology of Labor in the Early Republic. New York: Oxford University Press, 1990.

- Bracey, Christopher Alan, Paul Finkelman, and David Thomas Konig, eds. The Dred Scott Case: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives on Race and Law. Athens: Ohio University Press, 2010.

- Cutter, Barbara. Domestic Devils, Battlefield Angels: The Radicalization of American Womanhood, 1830–1865. DeKalb: Northern Illinois Academy Printing, 2003.

- Engs, Robert F., and Randall K. Miller, eds. The Nascency of the Grand Former Party: The Republicans' Start Generation. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2002.

- Etcheson, Nicole. Bleeding Kansas: Contested Liberty in the Ceremonious State of war Era. Lawrence: Academy Press of Kansas, 2004.

- Flexnor, Eleanor. Century of Struggle: The Women's Rights Movement in the United states of america. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Academy Press, 1975.

- Foner, Eric. Costless Soil, Free Labor, Costless Men: The Credo of the Republican Party Earlier the Civil War. New York: Oxford University Press, 1970.

- Grant, Susan-Mary. Due north over S: Northern Nationalism and American Identity in the Antebellum Era. Lawrence: Academy Press of Kansas, 2000.

- Holt, Michael F. The Rise and Fall of the American Whig Party: Jacksonian Politics and the Onset of the Ceremonious State of war. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999.

- Howe, Daniel Walker. The Political Culture of the American Whigs. Chicago: University of Chicago Printing, 1979.

- Jeffrey, Julie Roy. The Great Silent Army of Abolitionism: Ordinary Women in the Antislavery Movement. Chapel Hill: Academy of North Carolina Press, 1998.

- Jones, Martha South. All Bound Upwards Together: The Adult female Question in African American Public Culture, 1830–1900. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Printing, 2007.

- Kantrowitz, Stephen. More than Freedom: Fighting for Black Citizenship in a White Democracy, 1829–1889. New York: Penguin, 2012.

- McDaniel, W. Caleb. The Problem of Commonwealth in the Historic period of Slavery: Garrisonian Abolitionists and Transatlantic Reform. Baton Rouge: LSU Press, 2013.

- Oakes, James. The Scorpion'southward Sting: Antislavery and the Coming of the Civil War. New York: Norton, 2014.

- Potter, David M. The Impending Crisis, 1848–1861. New York: HarperCollins, 1976.

- Quarles, Benjamin. Allies for Freedom: Blacks and John Brown. New York: Oxford Academy Press, 1974.

- Robertson, Stacey. Hearts Beating for Freedom: Women Abolitionists in the Sometime Northwest. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Printing, 2010.

- Sinha, Manisha. The Counterrevolution of Slavery: Politics and Ideology in Antebellum Due south Carolina. Chapel Colina: University of N Carolina Press, 2000.

- Smith, Kimberly K. The Dominion of Vox: Riot, Reason and Romance in Antebellum American Political Thought. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1999.

- Varon, Elizabeth. Disunion! The Coming of the American Civil State of war, 1789–1859. Chapel Hill: Academy of Due north Carolina Press, 2008.

- Zaeske, Susan. Signatures of Citizenship: Petitioning, Antislavery, and Women's Political Identity. Chapel Hill: Academy of Northward Carolina Press, 2003

Notes

Source: https://www.americanyawp.com/text/13-the-sectional-crisis/

0 Response to "Reading Comprehension Question for Anthony Burns Book"

Post a Comment